If you were to freeze in place and time a square mile of land or a city so that you could study it like a diorama of the real life living on that particular chunk of dirt, where would your eyes land first, on what would you spend your gaze? First you might see the soaring and significant buildings, each one speaking with steel and stone the story this place would love to tell about itself. You might see people at work or play, bouncing from businesses to schools to jobs to homes. Some would traverse these stops with such ease that it would seem the land, buildings, and homes were made for them, aligned for their use. But who would you not see? Who would be missed in your first study of this place frozen in a moment? Would you see those laboring behind counters and mopping under stairs? Would you see the homes so poorly constructed that they could only be considered an afterthought—a construction subscript—meant to be in the shadow of those buildings with flashier glazing and ancient looking stones. Matthew Desmond, in his book Evicted, takes us to these places in American cities to display how a seemingly small legal mechanism like eviction pushes people far enough to the margins of cities and cultures that they live, work, survive mostly out of sight. American cities are built, quite literally, for some people and not others. Desmond’s argument is that the legal mechanisms of eviction are some of the general contractors of these hidden places in American cities. And it takes work to move your eyes past the things most towns want you to see, and take in full consideration those who are being actively hidden. Vision can be trained; it can also be fogged. Desmond writes, “the people I met in Milwaukee trained my vision by modeling how to see and showing me how to make sense of what I saw” (324).

The metaphor of seeing is helpful also for an approach to the issue of evictions from a place of faith. People of faith have eyes trained to see things differently. And for those with eyes to see, faith in the invisible helps bring things into the light. When the invisible is the lens, one is, hopefully, seeing the world—and its cities, cultures, systems, and people—slightly inside out. Jesus’ words in Luke help: “No one lights a lamp and hides it in a clay jar or puts it under a bed. Instead, they put it on a stand, so that those who come in can see the light. For there is nothing hidden that will not be disclosed, and nothing concealed that will not be known or brought out into the open.” This is the intersection of faith and evictions: the more that evictions are forcing people out of sight, the more urgent the call for people of faith to make them more visible. We are called to understand and help bring the unseen “out into the open.”

At base, eviction is a legal tool. At best it's a scalpel, helping property owners cut ties with damaging situations to their investments and property. Like all tools, their overuse and misuse can have devastating effect, like a surgeon showing up to a liver transplant with a chainsaw. The conversation about eviction is not just about legal or illegal expulsion of a tenant from a property, but it is also about the context in which these legal mechanisms happen. Laws are not impartial things but are active in a social context that guides their effects. Consider this legal opinion from a DC circuit court in 1968 responding to landlords evicting tenants for racial difference and for complaining about substandard building maintenance:

"In trying to effect the will of Congress and as a court of equity, we have the responsibility to consider the social context in which our decisions will have operational effect. In light of the appalling conditions and shortage of housing in Washington D.C. the expense of moving , the inequity of bargaining power between tenant and landlord, and the social and economic importance of assuring at least minimum standards in housing conditions, we do not hesitate to declare that retaliatory eviction cannot be tolerated" (Edwards vs. Habib D.C. Circuit 1968).

The court here indicates that the effects of the law, not just the law itself, make a difference in its just execution. In the current affordable housing crisis, eviction is playing an outsize role, carving up communities and pressurizing families.

From Evicted, there is no better example of these effects than a woman named Arleen whose family Desmond follows from housing security to insecurity and back again. Her situation displays an American situation:

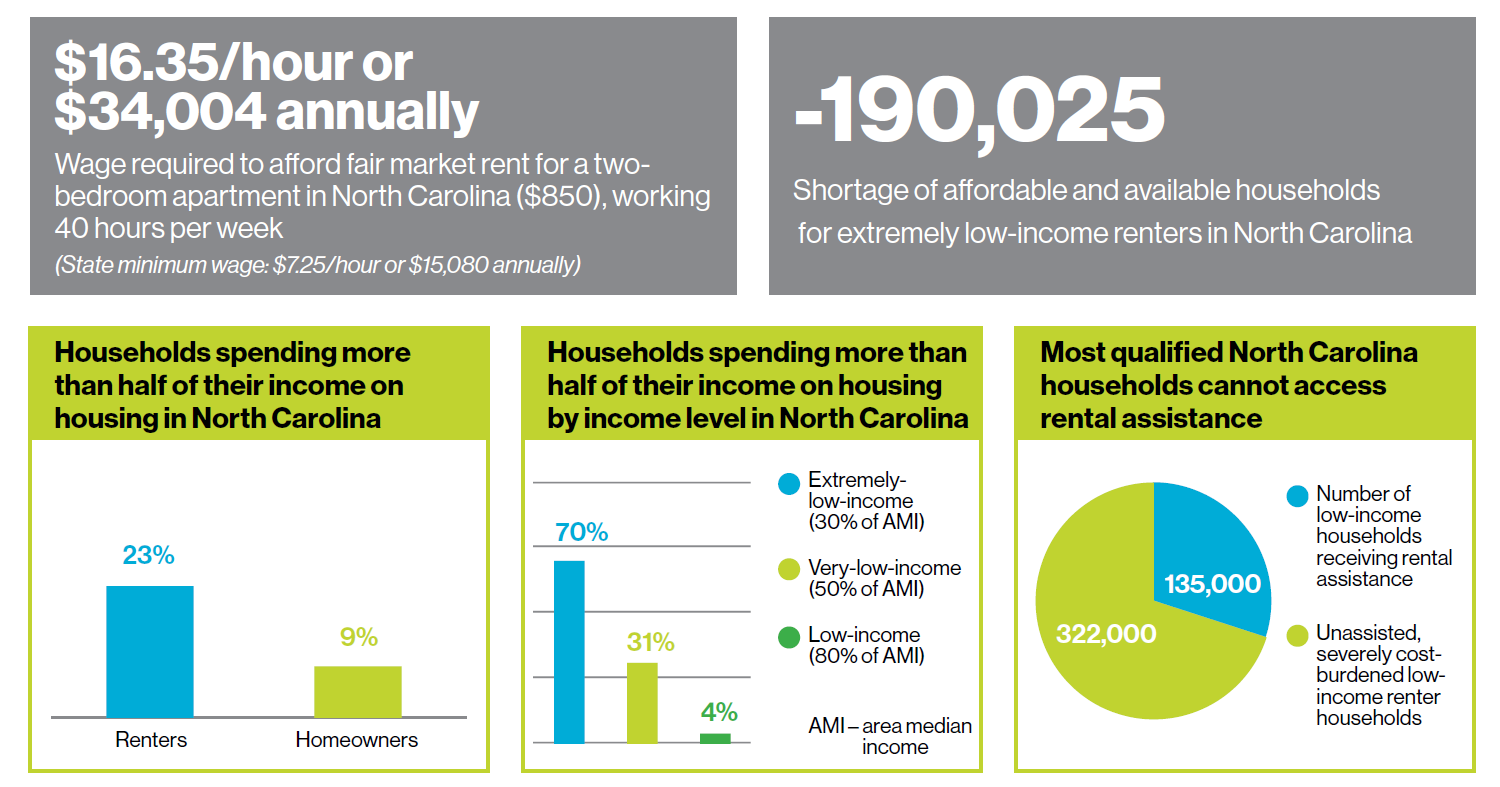

"Today, most poor renting families spend at least half of their income on housing costs...Incomes for Americans of modest means have flatlined while housing costs have soared...it has become harder for low-income families to keep up with rent and utility costs, and a growing number are living one misstep or emergency away from eviction" (Eviction Lab).

Arleen and her children were evicted from their longterm rental because a family funeral and a change in welfare status put her $870 behind on rent. Arleen had an option to pay; she could have signed her whole check over to the landlord, but “she thought it was better to be behind, and have a few hundred bucks in her pocket that to be behind and completely broke” (63). These kinds of tough decisions are, as the landlord said (not unsympathetically), “story of they life” (63). Arleen’s story is complicated, and would end up with her in court without a lawyer, packing up to leave during Christmas and beginning the process of finding new housing with an eviction on her record.

The title of this post, “Eighty-Nine Nos and Only One Yes,” is taken from the moment of simultaneous exhaustion and relief in the story of Arleen, who had made 90 calls to find new housing. Her story shows how the cords that bind renters to landlords, to cities, to substandard apartments, and to neighborhoods are tied in a knot so tightly that easy answers for blame or villainy fail to account for how bound together the problems remain. For Arleen in particular, regardless of the responsibility or irresponsibility, justice or injustice of her situation, she was alone and unseen by the community in the difficulty eviction brought to her door.

The title of this post, “Eighty-Nine Nos and Only One Yes,” is taken from the moment of simultaneous exhaustion and relief in the story of Arleen, who had made 90 calls to find new housing. Her story shows how the cords that bind renters to landlords, to cities, to substandard apartments, and to neighborhoods are tied in a knot so tightly that easy answers for blame or villainy fail to account for how bound together the problems remain. For Arleen in particular, regardless of the responsibility or irresponsibility, justice or injustice of her situation, she was alone and unseen by the community in the difficulty eviction brought to her door.

While eviction is a necessity to preserve property and owners' rights, the consequences are a thousand times more severe for those evicted: many families evicted once will remain housing insecure; add wage stagnation, rising rent, and neighborhood degradation and many find themselves calling on 90 classified ads hoping for the one "yes". Scarcity of shelter pressures those who are housing insecure into corners of cities that are darker and darker, less seen. “Poor families were often compelled to accept substandard housing in the harried aftermath of eviction. Milwaukee renters whose previous move was involuntary were almost 25 percent more likely to experience longterm housing problems than other low-income renters” (69). As you look for a home in those darker places, the more insecure your life is in those places and the more substandard the housing becomes. In supply and demand terms, “the high demand for the cheapest housing told landlords that for every family in a unit there were scores behind them ready to take their place. In such an environment, the incentive to lower the rent, forgive a late payment, or spruce up your property was extremely low” (47). A lack of a home and permanence has effects beyond fiscal status of tenants: “Studies also show that eviction causes job loss, as the stressful and drawn-out process of being forcibly expelled from a home causes people to make mistakes at work...one study found that mothers who experienced eviction reported higher rates of depression two years after their move” (Eviction Lab). The effects of eviction extend even beyond the one family. A neighborhood that has endured trauma is less likely to politically organize or “sense its potential.” “Milwaukee renters who perceived higher levels of neighborhood trauma—believing that their neighbors had experienced incarceration, abuse, addiction and other harrowing events—were far less likely to believe that people in their community could come together to improve their lives...a community that saw so clearly its own pain had a difficult time also sensing its potential” (181-182). Trauma, like evictions, keeps neighborhoods from seeing the good in themselves and therefore organizing around that good.

To see the true tragedy in this sort of neighborhood trauma requires an anthropology intolerant not just of the breakdown of individuals, but the breakdown of communities of individuals. The Christian tradition calls all humans images or reflections of God, not in isolation but in community. “The idea of the ‘image of God’...is not an idea which lives in a cosmological vacuum. It is an explicit call to form a new kind of human community in which the members, after the manner of the gracious God, are attentive in calling each other to full being in fellowship” (Brueggemann, Genesis, 35). Inherent in humanity, then, is a call toward one another, an expectation of real relationship to the other “full beings” around them. People of faith are called to see the image in all humans. A vision that helps to see them differently and, hopefully, see themselves differently. Desmond’s metaphor of how a community “sees” itself is instructive. How we see others, how we see communities leads to how we behave toward those communities. A colleague said, about Chapel Hill particularly, that some folks look at Chapel Hill through a fogged, nostalgia-glazed lens, where the bright and shiny Franklin Street or campus facades hide the real city. Those who can’t see Northside or the bar-back making 30% of the Area Median Income or can’t see the way neighborhood trauma, land loss, gentrification, or wage stagnation acts on a community won’t be able to act in their direction. One cannot move to help people out of a burning building if one cannot see the smoke coming from the windows. To see is to act, and to see people, though hidden, will offer an opportunity for action toward a full community, or in faith terms, full fellowship.

Eviction is a process inside a set of relationships that, in the end, have unbalanced, even unjust, effects on the people within a community. Eviction makes it difficult to see a whole community. WYNC’s radio show, On the Media, produced a series on the eviction crisis called The Scarlet E (linked in this newsletter) and it confirms, “families...live in your community, you just might not see them. They may be in shelters or broken up or couch surfing or pay by the week motels.” The problems that overuse and misuse of evictions pose are whole community problems; they involve all of us. Of all the people in a community, people of faith, guided by the sense that everyone reflects out the image of God, ought to be the first to see those that are being pushed to the sides. That the call to full human fellowship is a call to see everyone in a place. Then when a community stands with those who don’t have a place in a society, then those hidden places are a little less hidden. As The Scarlet E argues, in a nod toward both the law and community, landlords and tenants should consider, “jointly coming up with the terms for what it means to live in a community.” Desmond’s whole project was to show the knot of people and problems tied up together with evictions. It may be, with ways of seeing guided by the invisible, that a new kind of knot—a people acknowledging that those downtown need those being evicted—could begin to see one another and therefore live in a new way together, where “nothing hidden...will not be disclosed,” a way that might say “yes” more quickly to those needing safe, permanent housing.